The Recruiting Officer: Australia’s First Recorded Play

Written by Rebecca Vipond, RAHS Volunteer

When you hear the word ‘convict’, what comes to mind? Chain gangs? Cat o’ nine tails? How about theatre and play acting? On 4 June 1789, the birthday of King George III, a group of convicts performed Australia’s first recorded play at Sydney Cove. (1) The play was The Recruiting Officer by Irish playwright George Farquhar.

It is not surprising that a play was performed by the colonists. In the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, theatrical performances were popular, especially amongst lower social classes. (2) In fact, convicts performed a play on board the First Fleet ship Scarborough on 2 January 1788 before arriving at Sydney Cove. (3) At the time, actors were ‘regarded as “a rogue and a vagabond”’, little more than criminals, so the fact that actual convicts were the actors is unlikely to have bothered anyone. (4)

The Recruiting Officer was one of the most popular plays of the eighteenth century, first performed in 1706. (5) The plot was rousing and upbeat, a typical Restoration comedy. Set during the reign of Queen Anne, The Recruiting Officer concerns the exploits of army officers who come to the town of Shrewsbury to recruit soldiers for the army—and have fun with their girlfriends. But the officers’ girlfriends have recently become heiresses and are now too rich for their men. What follows is a romp of scheming as both the men and women resort to underhanded tactics, including cross-dressing and subterfuge, to achieve satisfaction in both the military and personal life. In this way, the title The Recruiting Officer can be understood to be about recruiting husbands as much as recruiting soldiers. (6) Its military themes would have resonated with the colonial audience, and this, along with the play’s popularity, was a likely reason for it being performed to celebrate the King’s Birthday. (7)

It is not known who in the colony initiated the idea to hold a play, but it was likely suggested by a convict. (8) The script of the play was probably brought to the colony by Captain John Hunter or another officer, but it is also possible that the convict actors performed from memory. (9) Regardless, the very fact that the colonists were willing to perform a play speaks much about their energy and heartiness. (10)

The Recruiting Officer was performed at night after a day of festivities, including gun salutes and a dinner for the officers at Government House. (11) The theatre venue was a hut fitted out with benches. (12) It probably had scenery made from paper, a common approach at the time. (13) There were about 65 people in the audience, drawn from the officers. It is unlikely that there were convicts in the audience. (14) The convict actors wore costumes that they made themselves, although military costumes may have been borrowed for the occasion. (15) Unfortunately, the names of the convict actors have not survived, but it is possible that some of the convicts who performed onboard the Scarborough were among them. (16)

Although he attended the performance, Governor Arthur Phillip did not mention it in his official reports. But Captain Watkin Tench and Judge Advocate David Collins both mentioned the performance in their accounts of the colony, and both men wrote about it warmly. (17)

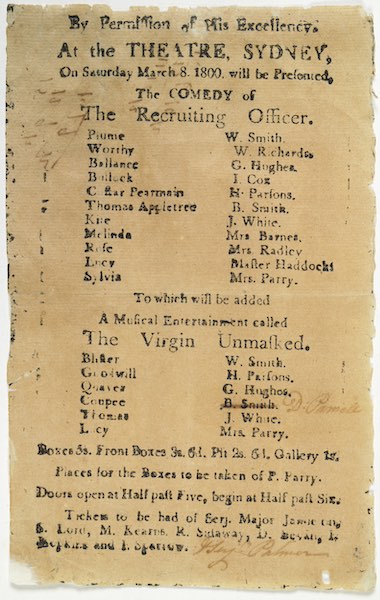

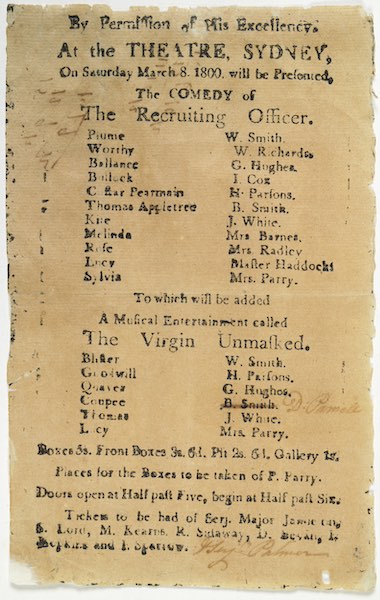

The King’s Birthday performance of The Recruiting Officer was not the last play performed in early New South Wales. In 1796, the first permanent playhouse was built in Sydney on the sight of the present-day Bligh Street. It was operated by convict Robert Sidaway and businessman John Sparrow. (18) It cost £100 to build and the price of admission was one shilling or foodstuffs to that value. (19) It was closed after two years. But theatre revived again. In 1800, there was another performance of The Recruiting Officer at the Sydney Theatre. A playbill from this performance still survives.

Playbill for ‘The Recruiting Officer’ and ‘The Virgin Unmasked’. Performed at the Sydney Theatre on Saturday, 8 March 1800 (Courtesy State Library of NSW)

So next time you hear the word ‘convict’, perhaps you will think of merry costumes and playful acting as much as leg irons and the Old Bailey.

References:

(1) Milestones in Australian History 1788 to the Present, compiled by Robin Brown, edited by Richard Appleton, William Collins Pty Ltd, Sydney, 1986, p. 5.

(2) Eric Irwin, Dictionary of the Australian Theatre 1788-1914, Hale and Iremonger Pty Limited, 1985, p. 12; Robert Jordan, The Convict Theatres of Early Australia, Currency House, 2002, pp. 5-21.

(3) Irwin, Dictionary of the Australian Theatre, p. 272.

(4) ‘Australian Stage Beginnings’, The World’s News, 13 January 1906, p. 9, <https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/128270738>, accessed 22 October 2024.

(5) Heather Blasdale-Clarke, ‘The Recruiting Officer’, Australian Historical Dance, updated 30 January 2012, <www.historicaldance.au/the-recruiting-officer>, accessed 15 October 2024.

(6) George Farquhar, The Recruiting Officer, edited by Tiffany Stern, Bloomsbury, London, 2010, pp. viii-ix, <https://books.google.com.au/books?hl=en&lr=&id=U0KJAwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP1&dq=the+recruiting+officer&ots=jXKFWAtR-1&sig=quEWPY0oi4QuPOwRoLue_rPSfbA&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=the%20recruiting%20officer&f=false>, accessed 22 October 2024.

(7) Jordan, The Convict Theatres of Early Australia, p. 32.

(8) Jordan, The Convict Theatres of Early Australia, p. 30.

(9) Blasdale-Clarke, ‘The Recruiting Officer’.

(10) Isadore Brodsky, Sydney Takes the Stage, Old Sydney Press, Neutral Bay, 1963, p. 4.

(11) John West and Jacqueline Kent, Theatre in Australia, Cassell Australia Limited, Stanmore, 1978, p. 9; Jordan, The Convict Theatres of Early Australia, p. 29.

(12) Irwin, Dictionary of the Australian Theatre, p. 272.

(13) Jordan, The Convict Theatres of Early Australia, p. 280.

(14) Jordan, The Convict Theatres of Early Australia, p. 31.

(15) Jordan, The Convict Theatres of Early Australia, p. 30-31; Blasdale-Clarke, ‘The Recruiting Officer’.

(16) Irwin, Dictionary of the Australian Theatre, p. 272.

(17) West and Kent, Theatre in Australia, p. 9.

(18) Irwin, Dictionary of the Australian Theatre, pp. 10-11.

(19) Brodsky, Sydney Takes the Stage, p. 5.

The 2023 NSW Premier’s History Awards, with $85,000 in prize money, were announced at the State Library of NSW on Thursday, 7 September.

The 2023 NSW Premier’s History Awards, with $85,000 in prize money, were announced at the State Library of NSW on Thursday, 7 September.