Researching Soldiers in Your Local Community

No Australian community is untouched by war. More than 300,000 Australians served in World War I from a population of less than five million. Two decades later, another million answered the call. Local memorials remember not only the tens of thousands who gave their life for their country, but the many more thousands who came home again, forever changed by war.

Historians speculate that every second family lost someone to the First World War. [1] The Australia of today is very different to the Australia of 1914 and the Australia of 1939. Not all of us have Anzac ancestors. But all of us live in a town or city, attend a school or university or church, walk past a village park or street corner, with a local war memorial.

As sources of local history, war memorials are invaluable. Each name has a story attached, and the increasing availability of online resources means that researching them is more achievable than ever. But where to begin?

This website aims to give you the tools to find out about your local soldiers, organised into eight themes. It complements our downloadable research guide, which outlines the online resources available for soldier research and how best to use them. Keep reading to discover key questions to ask about your local soldiers’ experience of war: why they enlisted, what the nature of warfare was really like, and how Australia has commemorated them, 100 years on.

Click the images to explore the research guide, local soldier stories, and YouTube video guides.

Your Title Goes Here

Recruitment

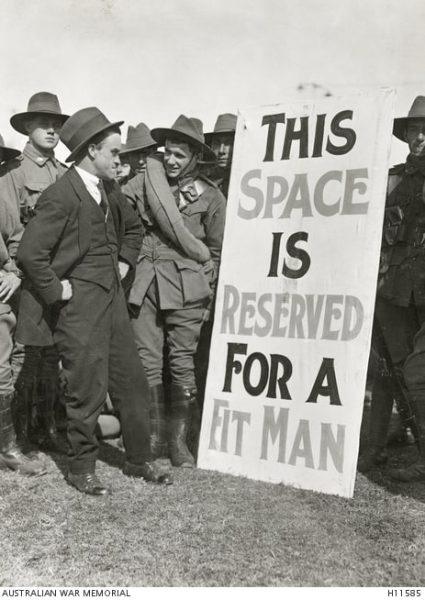

World War I recruitment: Australian soldiers on a recruitment drive encourage a man to enlist. Image courtesy Australian War Memorial.

Australia went to war in August 1914. Though far from the fighting, the thirteen-year-old Commonwealth nation felt an obligation to empire that was echoed among the country’s first enlistees. By the end of the year, 52,500 men had enlisted out of loyalty to the king, a desire for adventure, and a thirst to prove themselves among the world’s greatest nations. [1]

By the armistice of November 1918, two thirds of the 330,770 Australians who had served overseas had been killed or wounded. The glory of Gallipoli in 1915 had given way to the weary attrition of the Western Front, where three in four Australians who never returned home died. For a population of barely five million in 1918, such losses were steep indeed. [2]

Yet when world war broke out again in September 1939, Australians enlisted. Why, when they knew what lay in store?

Recruitment was the first step of the Australian soldier’s war experience. What did it look like in your community? Consider the roles played by propaganda and conscription. How did women become involved?

How was your local soldier recruited for war?

What to look for

- Attestation and enlistment papers (National Archives of Australia)

- Local news coverage (Trove)

- Soldier letters and diaries (Trove, Australian War Memorial, State Library of NSW)

Additional materials

‘Australia’s Fighting Sons’ – an overview of the resource Australia’s Fighting Sons of the Empire: Portraits and Biographies of Australians in the Great War and RAHS volunteer Trudy Holdsworth’s research into the soldiers featured, including difficulties with locating records and exemptions for service in the First AIF.

The Road to War

March 1941: Australian soldiers on leave in Athens, Greece, visit the Acropolis. Image courtesy Australian War Memorial.

While patriotism, duty to empire, and the desire to fight a ‘just’ war drove many Australians to enlist in the First and Second World Wars, for others, war was a chance to see the world.

This was especially true for World War I. The war presented the first opportunity for many Australians to travel overseas. It took them to Egypt, Greece, Turkey, Palestine, Belgium, France, and England. Troops of the First Australian Imperial Force (AIF) experienced these far-flung destinations not only down the barrel of a gun, but through the lens of a camera as well. While on leave, they toured the sites—London’s thoroughfares, the pyramids of Giza—for unlike other Allied forces, home was too far away to visit.

These men soon became known as ‘six-bob-a-day tourists’, after their army wages and generally adventurous attitudes. They wore the moniker with pride. [1]

The tradition continued in World War II, where Australians returned to fight in Europe and the Middle East as well as the Mediterranean, south-east Asia and the Pacific.

Where did your local soldier fight? How did they view the adventure of war?

What to look for

- War film and photography (Australian War Memorial, National Film and Sound Archive, State Library of NSW)

- Nominal rolls (Australian War Memorial, Department of Veterans’ Affairs)

- Local news coverage (Trove)

Life on the Front

War was an experience like no other. Australians in World War I endured the landings at Gallipoli, the desert terrain of the Eastern Front, and the battle of attrition in the trenches of Belgium and France. Men were soldiers, sailors, surgeons, pilots. Most women served as nurses, though others found work as ambulance drivers and even doctors. [1] The advent of mechanised warfare and its accompanying death toll prompted advancements in weaponry, medicine, and communications. It was a new war, a terrible war, and believed by many to be ‘the war to end all wars’.

It was not. World War II was declared within a generation. Australian servicemen and women faced even newer challenges: the gruelling conditions of the Kokoda campaign, the siege of Tobruk, the internment camps and forced labour endured by the 30,000 Australians taken as prisoners of war. For the first time, global war threatened Australia’s own borders. The lines between battle and home front blurred. [2]

What was the nature of warfare really like? How did your local soldier experience life on the front?

What to look for

- War film and photography (Australian War Memorial, National Film and Sound Archive, State Library of NSW)

- Soldier letters and diaries (Trove, Australian War Memorial, State Library of NSW)

- Service and casualty forms (National Archives of Australia)

Additional materials

‘Understanding the First AIF: A Brief Guide’ – a guide to understanding the history and structure of the First Australian Imperial Force (AIF) during World War I, so you may place your local soldier’s service in a more detailed context.

At 6 a.m. on 25 April 1915, soldiers of the First AIF disembark the troop ship on rope ladders for the infamous landing at Anzac Cove. Image courtesy Australian War Memorial.

4 October 1942: Men of the 2/31st Battalion negotiate a path through native cane. They would re-enter Kokoda a month later. Image courtesy Australian War Memorial.

Indigenous Service

2 November 1941: Privates George Leonard and Harold West embark at Sydney for the 2/1st battalion. Both men died in 1942. Image courtesy Australian War Memorial.

Hundreds of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men and women served in the World Wars. Their records are still being uncovered, and we may never know the identities of all those who fought, but current estimates suggest approximately 1,000 enlisted in the First World War, and 3,000 in the Second. [1]

During World War I, Indigenous men were prohibited from enlisting in the army under the Defence Act 1903. Many volunteered regardless, lying on their enlistment forms for the chance to fight for their country—a significant factor in the difficulty of identifying them today. Dwindling recruitment numbers in 1917 saw restrictions on enlistment eased, but Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander servicemen were still far from equal to their white Australian comrades. [2]

Thousands more enlisted in World War II, including Indigenous women in auxiliary efforts such as Oodgeroo Noonuccal, though they continued to face restrictions and discrimination. At least a dozen Indigenous soldiers died as prisoners of war. After both wars, however, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander veterans faced struggles other Anzacs did not: many were barred from membership in the Returned and Services League (RSL), and could not freely participate in Anzac and Armistice Day commemorations. [3]

Were there Indigenous servicemen and women in your community? How has the remembrance of their service changed over time?

What to look for

- Attestation and enlistment papers (National Archives of Australia)

- War film and photography (Australian War Memorial, National Film and Sound Archive, State Library of NSW)

- Nominal rolls (Australian War Memorial, Department of Veterans’ Affairs)

Prisoners of War

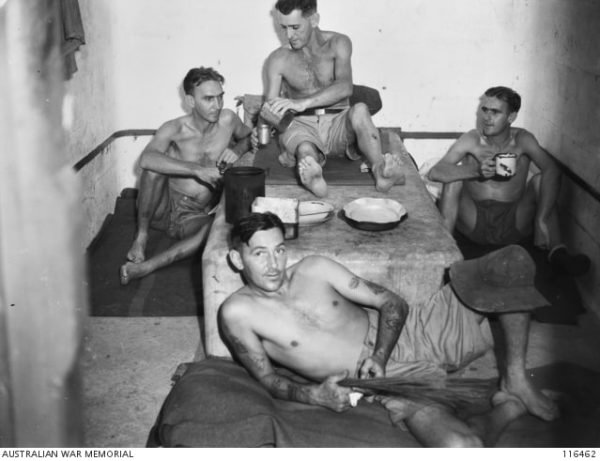

19 September 1945: Privates D. A. Meldrum, L. Coulson, and W. Oakley and (lying) Corporal L. W. Whisker of 8th Division show off cramped conditions in their cell at Changi prison camp after liberation. Image courtesy Australian War Memorial.

The prisoner of war experience does not fit comfortably within the accepted narrative of Australians at war. They were not tales of dramatic exploits in combat, of heroic sacrifice or victorious return. Most of those who died in internment camps succumbed to illness or disease. Though experiences differed between prison camps, captors, and wars, the dominant narrative of the Australian POW is one of suffering. [1]

History best remembers the 22,000 World War II POWs interned by the Japanese, mostly notably at the infamous Changi Prison or put to work on the Thai-Burma Railway, a forced labour camp with a death rate of one in five. Another 8,000 were captured by German and Italian forces. Less than 4,000 Australians became prisoners of war in World War I, mostly on the Western Front, though Ottoman forces captured 200 during the Gallipoli and Middle East campaigns. [2]

How did the prisoner of war experience differ from that of the regular serviceman or woman? Was your local soldier a prisoner of war? What did they endure?

What to look for

- Service and casualty forms (National Archives of Australia)

- Nominal rolls (Australian War Memorial, Department of Veterans’ Affairs)

- War film and photography (Australian War Memorial, National Film and Sound Archive, State Library of Australia)

On the Home Front

1943: Aircraftwomen Nancy King and Viola Peterson of the Women’s Auxiliary Australian Air Force (WAAAF) load a Vickers Gun with ammunition. Image courtesy Australian War Memorial.

World War I introduced the notion of ‘total war’ to the Australian population: not only did countries commit soldiers to the cause, but civilian industry and people as well. Australia was further from the reality of the war than most other Allied combatants, but those on the home front still played their part. Roles changed for women in particular: not only did they fill jobs traditionally held by the men who were away at war, they mobilised in organisations and fundraising drives such as the Australian Red Cross Society, the Country Women’s Association, soldiers’ comfort funds, and Jessie Street’s ‘sheepskins for Russia’ appeal. Vera Deakin established the Red Cross Wounded and Missing Enquiry Bureau, its primary purpose to find answers for families with wounded, missing, or captive soldiers. [1]

World War II brought conflict to Australia’s doorstep. The bombing of Darwin by the Japanese in 1942 and the presence of American servicemen in Australian towns and cities reinforced the notion of ‘total war’ like never before. Women rose to the occasion. The Australian Women’s Land Army was formed in 1942 to replace male farm workers who had gone to war. Each branch of the armed forces also formed a women’s auxiliary corps, where they worked as radio operators, mechanics, drivers, and more. [2]

How did your community respond to war?

What to look for

- Local news coverage (Trove)

- War film and photography (Australian War Memorial, National Film and Sound Archive, State Library of NSW)

- Australian Women’s Land Army records (National Archives of Australia)

Soldiers Return

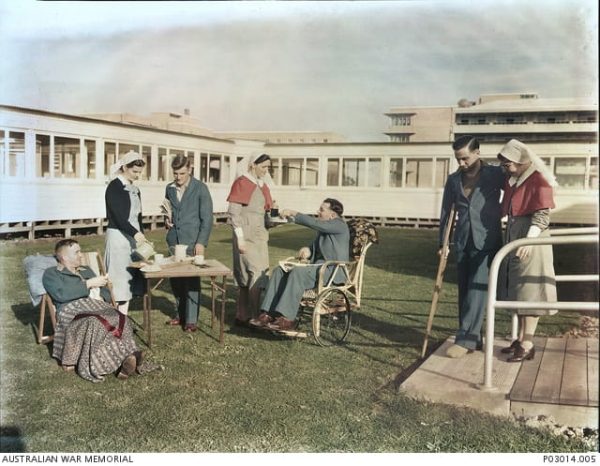

1942: Convalescing soldiers at the Heidelberg Repatriation Hospital in Victoria, accompanied by nurses (in red) and a volunteer from the Voluntary Aid Detachment (in blue). Image courtesy Australian War Memorial.

Returned soldiers were gradually repatriated back into Australian society. The impact of the wars had changed them forever. One in five Australians who served abroad in World War I never came home again. [1] Less Australians gave their life in World War II, but more men and women served. Many, if not most, of those who returned home were scarred, sometimes physically, often psychologically. They were returning to a country that had changed without them: divided over conscription in World War I and loyalty to empire in World War II, with women now visible in the workforce.

The 1916 Soldier Settlement Scheme was an attempt to smooth the transition between soldier and civilian life by offering returned servicemen a stable livelihood and income, with the added benefit of stimulating the regional economy. By 1924, more than 23,000 ex-soldiers had traded in their rifles for the plough. In popular imagination, the scheme merged the two iconic Australian identities of bushman and digger, but the reality was far from the bucolic dream. [2]

Plots of land were often small, with poor quality soil. Many soldiers who took up the scheme had no prior experience working the land. The declining economy culminating in the Great Depression of the 1930s only added to the stresses of the already suffering returned soldier. Despite the plots allotted for the scheme being on stolen Aboriginal land, only three Indigenous ex-servicemen were successful in their applications: two in Victoria and one in New South Wales. [3]

How many of your town’s soldiers returned home from war? How many did not? Can you find out if your local soldier participated in the soldier settlement scheme? How did they fare? What was life really like for the ex-serviceman or woman?

What to look for

- Local news coverage (Trove)

- Nominal rolls (Australian War Memorial, Department of Veterans’ Affairs)

- Soldier Settlement Indexes (NSW State Archives and Records)

Memory and Memorials

The first Australian monument honouring ‘men who fell’ was built in the nineteenth century to commemorate the Eureka Stockade. More recently, efforts have been made to remember in monumental form the Indigenous lives lost to frontier violence since 1788.

The first World War I memorial was unveiled in Balmain, Sydney, on 23 April 1916, just in time for the first anniversary of the landings at Gallipoli. Today, Australia is a country of war memorials, with 1,500 dedicated to the First World War alone: about one for every forty men who died. [1] Across the country, war memorials act as repositories for grief, shrines for prayer, sites of memory and healing. They work alongside other national forms of remembrance, notably Armistice Day on 11 November and Anzac Day on 25 April.

Anzac today is a cultural touchstone across the nation, removed from its original status as mere anniversary and acronym, now imbued with significance, reverence, and power—said to be emblematic of the Australian character and soul.

How was your local soldier remembered? How does your community commemorate war? Have perspectives changed over time? How do you understand the nature and legacy of the Anzac legend within your community?

What to look for

- Local news coverage (Trove)

- Soldier cemeteries and memorials (National War Memorials Register, Commonwealth War Graves Commission)

- War film and photography (Australian War Memorial, National Film and Sound Archive, State Library of NSW)

February 1919: Sergeant H. M. Skinner of the 27th Battalion lays flowers on the French grave of Private R. A. Shawyer who died of his wounds, 21 May 1918. Image courtesy Australian War Memorial.

25 April 1938: A boy places a wreath on the Martin Place Cenotaph, Sydney, during the Anzac Day march. The world would go to war again the following year. Image courtesy Australian War Memorial.

References

Introduction

[1] Ken Inglis assisted by Jan Brazier, Sacred Places: War Memorials in the Australian Landscape (Melbourne: Melbourne University Publishing, 2005), 97.

Recruitment

[1] Bill Gammage, The Broken Years: Australian Soldiers in the Great War (Canberra: Australian National University Press, 1974), 7.

[2] Inglis, Sacred Places, 91-92.

The Road to War

[1] Richard White, ‘Australian Tourists in Britain, 1900–2000’, in Australians in Britain: The Twentieth-Century Experience, ed. Carl Bridge, et al. (Melbourne: Monash University ePress, 2009), 11.1-11.15.

Life on the Front

[1] Heather Sheard, ‘Australia’s women doctors in the First World War’, VIDA, Australian Women’s History Network, 21 March 2017, https://www.auswhn.com.au/blog/women-doctors/.

[2] ‘Australian Prisoners of War 1940-1945’, Anzac Portal, Department of Veterans’ Affairs, accessed 24 May 2021, https://anzacportal.dva.gov.au/wars-and-missions/world-war-ii-1939-1945/resources/australian-prisoners-war-1940-1945.

Indigenous Service

[1] ‘Indigenous defence service’, Australian War Memorial, last updated 10 March 2021, https://www.awm.gov.au/articles/encyclopedia/indigenous; ‘Indigenous service’, Anzac Portal, Department of Veterans’ Affairs, accessed 24 May 2021, https://anzacportal.dva.gov.au/wars-and-missions/world-war-ii-1939-1945/resources/all-australian-homefront-1939-1945/indigenous-service.

[2] Philippa Scarlett, ‘Aboriginal service in the First World War: Identity, recognition and the problem of mateship’, Aboriginal History 39 (2015): 163-181; ‘Aboriginal service during the First World War’, Australian War Memorial, last updated 20 December 2019, https://www.awm.gov.au/about/our-work/projects/indigenous-service.

[3] ‘Indigenous defence service’, AWM.

Prisoners of War

[1] Kate Ariotti, ‘“I’m awfully fed up with being a prisoner”: Australian POWs of the Turks and the Strain of Surrender’, Journal of Australian Studies 40, no. 3 (2016): 276-290; Stephen Garton, The Cost of War: Australians Return (Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 1996), ch. 7.

[2] Kate Ariotti, Captive Anzacs: Australian POWs of the Ottomans during the First World War (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018), introduction.

On the Home Front

[1] ‘Vera Deakin’, Australian War Memorial, accessed 24 May 2021, https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/P156.

[2] ‘Roles for women in WWII’, Ergo, State Library of Victoria, accessed 24 May 2021, http://ergo.slv.vic.gov.au/explore-history/australia-wwii/home-wii/roles-women-wwii.

Soldiers Return

[1] Inglis, Sacred Places, 91-92.

[2] ‘Year Book Australia, 1925’, Australian Bureau of Statistics, https://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/featurearticlesbyCatalogue/72BB159FA215052FCA2569DE0020331D.

[3] Tim Lee, ‘“They were back to being black”: The land withheld from returning Indigenous soldiers’, ABC News, 14 April 2019, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-04-14/land-withheld-from-indigenous-anzacs/10993680.

Memory and Memorials

[1] Inglis, Sacred Places, 18, 107; Tim Lee, ‘Set in stone: “A nation of small town memorials”’, ABC News, 24 April 2010, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2010-04-24/set-in-stone-a-nation-of-small-town-memorials/408832.

Author: Elizabeth Heffernan, RAHS Intern

Web design: Elizabeth Heffernan, RAHS Intern

Header image: Australian War Memorial, E04795

This project was supported by Create NSW through the Arts Rescue and Restart Package – Stage 2.