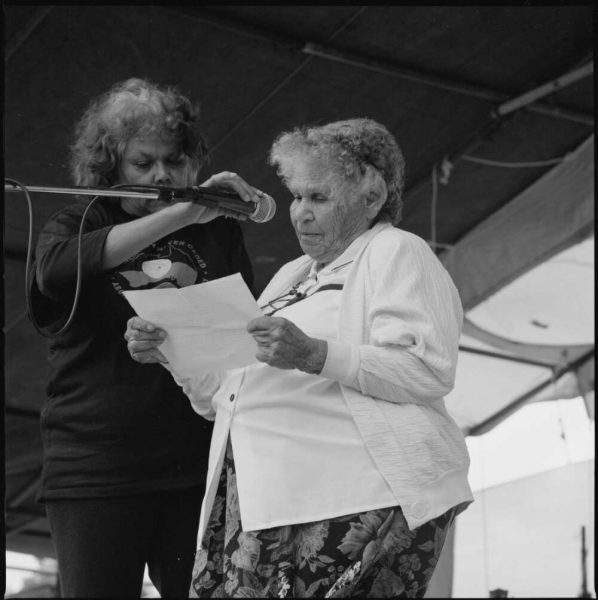

Australian swimmers Fanny Durack and Mina Wylie played a major part in this historic event. Winning gold and silver in the 100m freestyle, they were the first Australian women to become Olympic champions. They were also the first women in the world to win Olympic medals in swimming—joined by England’s Jennie Fletcher, who placed bronze.

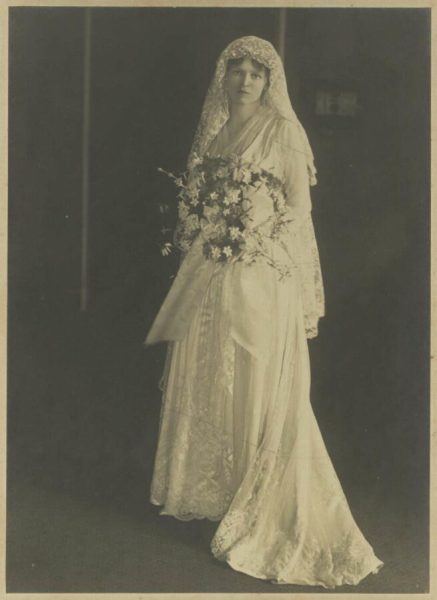

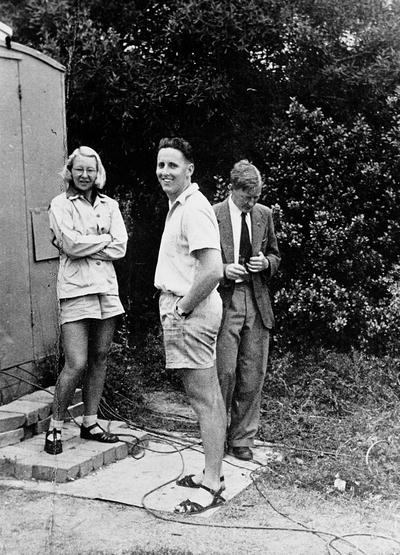

AUSTRALIAN SWIMMERS FANNY DURACK AND MINA WYLIE WITH BRITISH SWIMMER JENNIE FLETCHER AT STOCKHOLM 1912. IMAGE COURTESY NATIONAL MUSEUM OF AUSTRALIA.

It was not an easy route to get there. The NSW Amateur Swimming Association, to which both Fanny and Mina belonged, did not believe women should appear in competitions where men were present. Australian officials also maintained there was only enough money to send male athletes to the 1912 Games. Only a significant outpouring of public support—and funding—ensured the Olympic campaign of both women. It was a decision which changed Fanny and Mina’s lives—and the world of women’s competitive swimming—forever. [2]

Fanny and Mina were born two years apart, raised in North Sydney. Fierce friends and rivals, they trained together at Wylie’s Baths in Coogee, built for Mina by her father in 1907. Though Fanny was the favourite for Olympic gold in 1912, Mina was still tipped for a medal. They lived up to expectations, Fanny bringing home a world record of 1:19.8 in the 100m freestyle along with the gold. [3]

Stockholm was the highlight of both Fanny and Mina’s careers. They faced difficulty navigating the Amateur Swimming Association’s rules for competitive swimming post-war, and only weeks prior to the 1920 Antwerp Games, Fanny suffered an appendectomy followed by typhoid and pneumonia, causing her to withdraw. She retired the following year. [4]

Mina continued to win titles and hold records in freestyle, breaststroke, and backstroke long after Fanny’s retirement. She then went on to teach swimming at the Presbyterian Ladies’ College in Pymble for over forty years. Both women were inducted into the International Swimming Hall of Fame at Fort Lauderdale, Florida, and are remembered for blazing the trail for later generations of Australian swimmers like Dawn Fraser and Emma McKeon. [5]

Today the women’s 100m freestyle record stands at 51.71, held by Sweden’s Sarah Sjöström—almost thirty seconds faster than Fanny’s 1912 time. But women today can train and compete in the same pools as men; in 1912, mixed bathing was still banned. As of Tokyo 2020, women can now compete in all the same distances as men; in 1912, only the 100m freestyle and the 4x100m freestyle relay were permitted. They can also compete wearing streamlined, speed-efficient swimsuits; a far cry from the heavy woollen costumes of Fanny and Mina’s time. [6]

Women in sport have come a long way since Stockholm 1912, but Fanny and Mina’s achievements are remarkable all the same. As the Sydney Barrier Miner newspaper wrote about Fanny in 1912:

If there is any athlete in Australasia who should go to the great contests, it is this young Sydney swimmer … If this formidable array [of titles] is not a record that Australia should be proud of in one of her daughters, then there is no such thing as national pride. [7]

References:

[1] John Lohn, ‘Women’s History Month: Aussie Fanny Durack a Pioneer in Olympic Women’s Swimming As The First Champion’, Swimming World Magazine, 1 March 2021, https://www.swimmingworldmagazine.com/news/womens-history-month-aussie-fanny-durack-a-pioneer-in-olympic-womens-swimming-as-the-first-champion/; Pete Smith, ‘A century before Cate Campbell there was Mina Wylie’, SBS, 8 August 2016, https://www.sbs.com.au/topics/zela/article/2016/08/08/century-cate-campbell-there-was-mina-wylie.

[2] Warwick Hirst, ‘Wylie, Wilhemina (Mina) (1891–1984)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/wylie-wilhemina-mina-15656/text26851, published first in hardcopy 2012, accessed online 26 March 2022; Helen King, ‘Durack, Sarah (Fanny) (1889–1956)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/durack-sarah-fanny-6063/text10375, published first in hardcopy 1981, accessed online 26 March 2022.

[3] Hirst, ‘Wylie, Wilhemina (Mina)’; King, ‘Durack, Sarah (Fanny)’.

[4] King, ‘Durack, Sarah (Fanny)’.

[5] Hirst, ‘Wylie, Wilhemina (Mina)’.

[6] ‘A picture in time: Fanny Durack and Mina Wylie at the 1912 Olympics’, The Guardian, 12 July 2021, https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/ng-interactive/2021/jul/12/a-picture-in-time-fanny-durack-and-mina-wylie-at-the-1912-olympics; ‘12 July 1912: Fanny Durack becomes the first female Olympic swimming champion’, Olympics.com, 12 July 2019, https://olympics.com/en/news/12-july-1912-fanny-durack-becomes-the-first-female-olympic-swimming-champion.

[7] ‘12 July 1912’.