Written by Elizabeth Heffernan, RAHS Volunteer

To celebrate Women’s History Month in 2020, the Royal Australian Historical Society will continue our work from last year to highlight Australian women that have contributed to our history in various and meaningful ways. You can browse the women featured on our webpage, Women’s History Month.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are advised that this webpage contains the images and names of people who have passed away.

Known as Mum Shirl among the Aboriginal community, Shirley Coleen Smith was a fierce Wiradjuri activist and selfless caretaker throughout her lifetime.

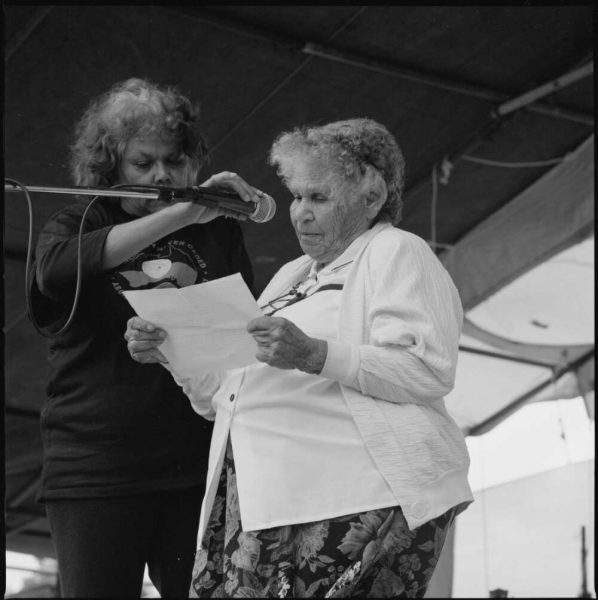

Mum Shirl (Mrs Shirley Smith) speaking at the Australia Day ceremony at the Aboriginal Tent Embassy in front of Old Parliament House, Canberra, 26 January 1998 / Loui Seselja [Image courtesy National Library of Australia, NL38352]

Shirley suffered from epilepsy. When she was young there was no medication for it, and the illness severely impaired her access to a formal education. She was instead taught by her grandfather, and learned to speak sixteen different Aboriginal languages. She could not read or write much English, but this never stopped her. She would even go on to publish an autobiography in 1981, written with the assistance of Bobbi Sykes. [2]

Shirley moved to Sydney at a young age and spent most of her life in the city. It was there she met her husband, professional boxer Cecil Hazil known by his fighting name Darcy Smith. The couple had a daughter together, Beatrice. When Shirley was pregnant she moved to Kempsey on the NSW north coast with her husband’s family, but returned to Sydney soon afterwards when she discovered the local hospital was segregated. Shirley raised her daughter for a short time, but as her epilepsy made it hard to find and maintain a job, she later sent her to Kempsey to be raised by her father. [3]

Shirley was passionate about helping others. When her brother Laurie was imprisoned, she took to visiting him and his fellow inmates regularly. When Laurie was released, Shirley continued to make her visits, earning her the endearing nickname. Asked about her relationship to the prisoners she saw, Shirley famously replied: “I’m his mum.” The Department of Corrective Services acknowledged Shirley’s tireless voluntary work with a pass allowing her access to all its prisoners. The Child Welfare Department and Newtown police also began to rely on her help in court cases involving the Aboriginal community, for which she was given a small courtesy fee. [4]

It was in the 1970s that Shirley’s activism gained traction. She helped to establish the Aboriginal Legal Service, the Aboriginal Medical Service, the Aboriginal Black Theatre, the Aboriginal Tent Embassy, the Aboriginal Children’s Service, the Aboriginal Housing Company, and the Detoxification Centre. Shirley worked for the Aboriginal Medical Service for many years after its foundation. She also independently helped a number of Aboriginal Australians, providing food and shelter to those in need and friendship to all. Although her invalid pension was often the only income she had, Shirley readily shared it with the rest of the community. Though this often led to her power being cut off, Shirley never stopped giving to those who, in her eyes, needed it more. [5]

Alongside other Sydney Aboriginal activists, Shirley supported the Gurindji land rights claim, and spoke alongside Gough Whitlam at a campaign event for the Labor Party in 1972. She had learned about politics later in life but that never stopped her from becoming involved. For her efforts, Shirley was honoured as a Member of the British Empire in 1977 and a Member of the Order of Australia in 1985. At her MBE ceremony she experienced conflicting emotions: “As it was getting close to my turn, it was flashing into my mind the numbers of places where I couldn’t get served; how I had had to sit on the ground at the front of the picture theatre as a child in the roped off section that Blacks had to sit in … the camps and shacks that Blacks were having to live in all over this country that was, after all, ours – and here I was, standing up here with all these well-dressed and fashionable people”. [6]

Even with all her honours and awards, Shirley’s pass to visit prisoners was revoked after her MBE. In her later years, the Department of Aboriginal Services made it difficult for Shirley to continue her work with the Aboriginal Medical Service. She often felt frustrated at a system and society that, when one Aboriginal person committed a crime, most often as a result of discrimination and disadvantage, turned the blame on the Aboriginal community as a whole. [7]

Yet Mum Shirl never gave up. Throughout her lifetime she helped raise over sixty children in need of a home; improved the lives of countless homeless, disadvantaged, and at risk Aboriginal Australians; and raised awareness for the land rights struggle that remains ongoing. Of her awards, Shirley remarked: “They must be worth something in the end, mustn’t they?” [8] But it was Shirley herself who was worth something – who was worth everything, to those who truly needed her.

References:

[2] Chrissie Crispin, ‘Significant Aboriginal women: Shirley Colleen Smith’, Research Services City of Parramatta Council, 10 July 2018, <http://arc.parracity.nsw.gov.au/blog/2018/07/10/significant-aboriginal-women-shirley-colleen-smith/>, accessed 3 March 2020.

[3] ‘Biography’.

[4] ‘Biography’.

[5] Clare Land, ‘MumShirl’, The Australian Women’s Register, 3 September 2002, <http://www.womenaustralia.info/biogs/IMP0092b.htm>, accessed 3 March 2020; ‘Shirley Smith’, Collaborating for Indigenous Rights, <https://indigenousrights.net.au/people/pagination/shirley_mumshirl_smith>, accessed 3 March 2020.

[6] Land, ‘MumShirl’.

[7] Land, ‘MumShirl’; Smith, Mum Shirl, pp. 7, 111, in ‘Biography’.

[8] Land, ‘MumShirl’.

0 Comments