Written by RAHS Volunteer and Copywriter Christina King

This blog post is part of a series entitled ‘The Convict Experience: Love, Life and Liberty Beyond the Chains’. Each month we will explore a different – and often rather unusual – type of primary evidence historians can use to hear convict voices telling their own stories.

Previous editions on Convict Tattoos and Love Tokens are still available to read online.

What was flash language and who used it?

Originating in the criminal underworld of Britain, flash language developed as a means of communication amongst the convicts of the new colony.[1] In fact, flash terms and phrases were so incomprehensible to the authorities, that ‘in the early days of colonisation a court-appointed interpreter was often required to translate the depositions of the witnesses and the accused.’[2]

‘Flash’ was the informal description for the language; the term used in more formal contexts was ‘cant’ language.[3] It is difficult to ascertain whether all convicts would have been familiar with the vocabulary of flash language. Certainly though, enough of them utilised it to have earned themselves the title of “flash men”.

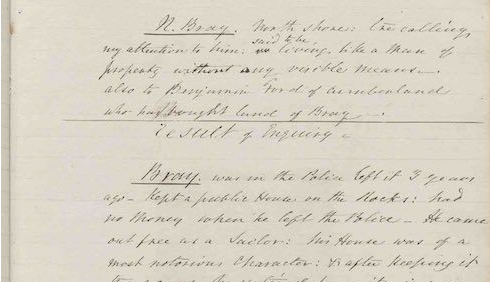

Who were these people though? One surviving primary source provides a clue into individual “flash men” and their stories. The source is entitled simply the Registry of Flash Men and is a compilation of ‘persons of interest’ to the police. Accumulated between 1841 and 1846, not only does the registry list the convicts’ names, but also details including known aliases and associates, appearance, occupation, temperament, and even detail on whether they arrived in NSW as a convict or a free settler. Written mostly in the hand of Commissioner of Police William Augustus Miles, the work seems to have been one of a few registers. Sadly, only this volume has survived. [4]

Why did flash language develop?

Simon Barnard explains that ‘communicating in slang provided criminals with the means to deceive and confuse the authorities.’ [5] In fact, flash language proved to be a highly effective ‘form of subversion of authority’ on the part of the convicts in a world where they had little voice, freedom, or control over their lives. [6]

Perhaps inevitably, the literate aristocracy has been largely responsible for the recorded usage of criminal slang. One important exception, however, is the work entitled A New and Comprehensive Vocabulary of the Flash Language published in 1819 and compiled by convict James Hardy Vaux. Despite being raised as a gentleman from a respectable family, Hardy Vaux rejected the expectations of aristocratic life and instead found himself convicted and transported to NSW three times in 1801, 1810, and again in 1831. [7]

How was flash language received in the colony?

British marine officer Captain-Lieutenant Watkin Tench was so opposed to the use of flash language amongst prisoners that he believed its very usage to be a barrier to convicts reforming their behaviour. He advocated ‘an abolition of this unnatural jargon [to] open the path to reformation… [and] a return to honest pursuits and habits of industry’. [8]

In addition, many writers and journalists of the day either omitted or edited flash slang from their writing, ‘fearing that slang would normalise and perpetuate criminal behaviour.’ [9]

Interestingly though, Simon Barnard outlines that James Hardy Vaux’s dictionary, upon its release in Australia, was so in demand that it ‘appears to have sold out.’ Various accounts of lawyers being in urgent need of a copy of the dictionary in Van Diemen’s Land also suggest that members of the free settler class saw some value in the work, if only to be able to better understand the convict language. [10]

Examples of flash language

James Hardy Vaux’s original dictionary was an addition to his larger work Memoirs of James Hardy Vaux. The glossary of convict slang was originally dedicated (whether tongue-in-cheek is difficult to ascertain) to ‘Thomas SkoTTowe, Esq., of His Majesty’s 73d Regiment, Commandant of Newcastle, in the Colony of New South Wales, and one of His Majesty’s Justices of the Peace for that Territory… With the utmost deference and respect’. [11] Dedicating the dictionary to the commandant of the Newcastle Penal Station, where Hardy Vaux was imprisoned at the time of his writing it, perhaps gives historians an insight into the personality of a particularly interesting colonial character.

Although a secondary source, Simon Barnard’s recently published work on James Hardy Vaux’s compilation of criminal slang provides an alphabetised – and hilariously illustrated – list of flash terms from Hardy Vaux’s original memoir.

The dictionary is a fascinating read, including words from ‘unthimble’ (a verb, meaning to rob a man of his watch, since a ‘thimble’ was also a flash term for ‘watch’), through to a ‘lag ship’ (a term for the ships used to transport convicts to NSW) and particularly colourful terms like a ‘bum-trap’ (a bailiff or sheriff’s officer, a highly unpopular position in the colony). [12]

What does flash language imply about the convict experience?

Certainly, the use of cant or flash slang amongst convicts outlines another interesting form of subversion of authority in a world where colonial prisoners had very little freedom. The incomprehensible nature of the language – seen in the popularity of Hardy Vaux’s dictionary as well as the necessity for interpreters in court proceedings – really provided convicts with a secret means of communication and therefore, a tiny form of freedom of speech, at least amongst themselves.

References:

[1] Amanda Laugesen, Convict Words: Language in Early Colonial Australia (South Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 2002), viii.

[2] Simon Barnard, James Hardy Vaux’s 1819 Dictionary of Criminal Slang, and other impolite terms as used by the Convicts of the British Colonies of Australia (Melbourne: Text Publishing, 2019), v.

[3] Barnard, Vaux’s 1819 Dictionary, v.

[4] NSW State Archives & Records, Series NRS-3406, Registry of Flash Men, (Accessed 9 September 2019).

[5] Simon Barnard, ‘“Is that bum trap missing a flesh-bag?” A guide to Australia’s convict slang’, The Guardian, published 20 August 2019, (Accessed 4 September 2019).

[6] Laugesen, Convict Words, viii.

[7] Barnard, Vaux’s 1819 Dictionary, vi.

[8] Watkin Tench, Sydney’s First Four Years, being a reprint of A Narrative of the Expedition to Botany Bay and A Complete Account of the Settlement at Port Jackson (Angus Robertson, Sydney, 1961), quoted in Laugesen, Convict Words, ix.

[9] Barnard, Vaux’s 1819 Dictionary, vi.

[10] Barnard, Vaux’s 1819 Dictionary, v.

[11] James Hardy Vaux, Memoirs of James Hardy Vaux in Two Volumes, Volume 1, (London: W. Clowes, 1819).

[12] Barnard, Vaux’s 1819 Dictionary, 29, 138, 292.

0 Comments